WRITING

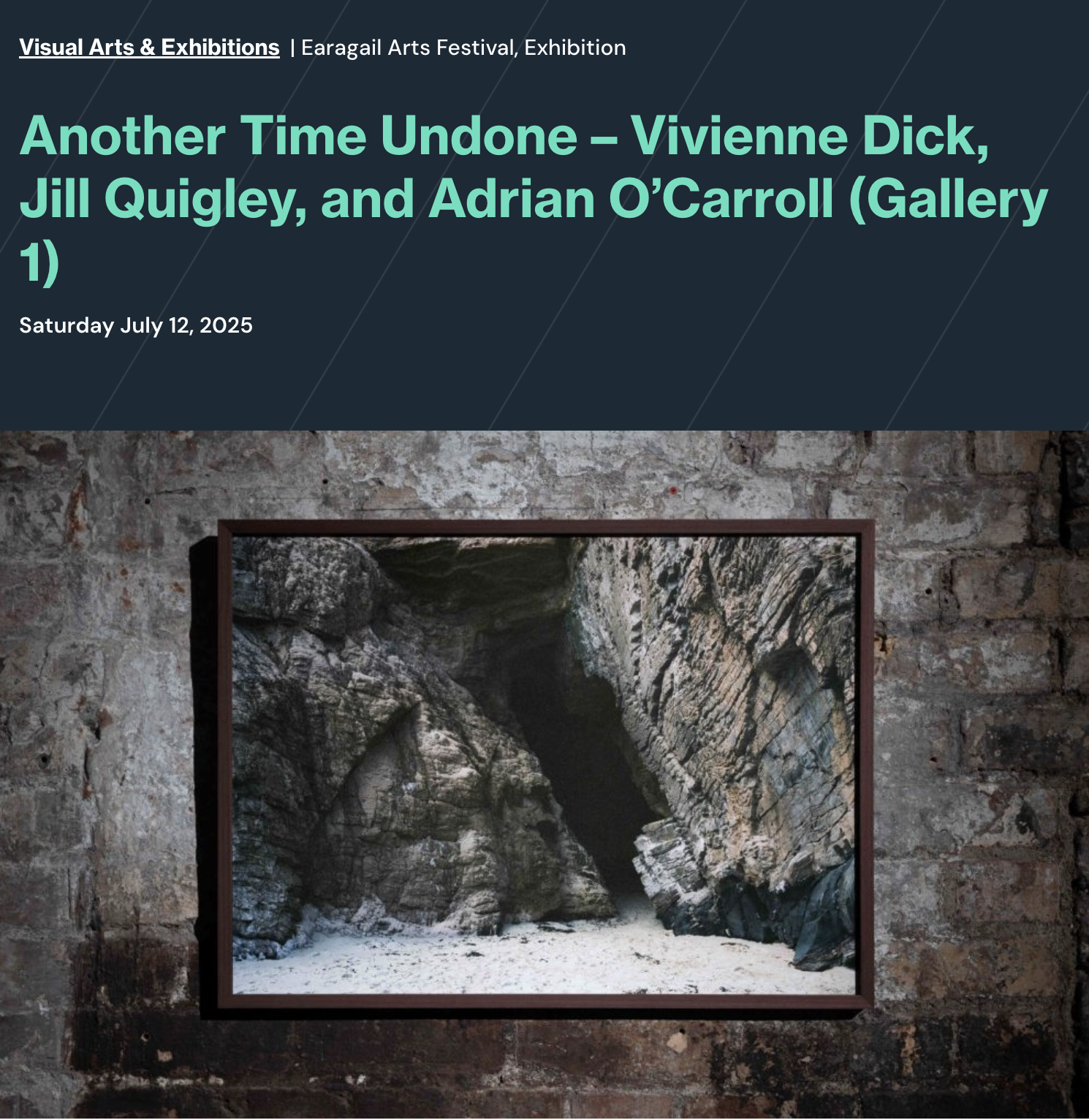

Another Time Undone

*

Home is a word brimming with emotion, expectation and contradiction. It is never just a place, but a profound experience that both shapes us and is shaped by us. Home is somewhere essential to have, if only to give us somewhere we can leave, secure in the knowledge that there is a place to return to. It is often seen as safe, but also as static and dull; it is the place we leave behind in order to do something meaningful. It is elusive, maybe as much a feeling or a relationship as it is a solid structure or a dot on a map.

Home is an idea whose complexity defies the simple fixity of time and place. We talk about making a home, being at home, making yourself at home, or feeling at home, all common phrases that are resonant with meaning and whose presence or absence is felt deeply. The term nostalgia reflects some of the emotional affect of this connection. Combined from the Greek words nostos (return home) and algia (pain, longing), it was coined by a doctor who noted a sickening in Swiss soldiers missing their Alpine homes. Home is one of our most significant sites for making and storing meaning, memory and identity. It is an ideal; of course, ideals can never really be lived up to.

The Cure song that lends the exhibition its title expresses the futility of attempting to reconnect with place in another time, and the beautiful bleakness of memory. It speaks of the poignancy of disconnection and asynchrony. We do not return to the places of our past as they were; we return to them altered, by time, by our (mis)remembering, by our own changing selves.

*

Donegal itself exists in a kind of liminal space. It is a borderland, not just geographically but culturally and psychologically. It is the North to Southerners, and the South to Northerners. The accent is distinctive, yet hard to place. It is a county with both staggering beauty and difficult history. The artists in this exhibition all grew up in Donegal and were drawn elsewhere, by dreams or circumstances.

Like the curator, I am a Northerner who grew up in the strange, grey time of the euphemistically-named Troubles. For us, Donegal was a place to escape to, a place of freedom and space: another time, outside our own. Away from the elephant in the room, we could forget the gnawing anxiety, the watchfulness, the grindingly familiar head down, mouth shut. Donegal had mystical connotations for Northerners of our generation. Now, I wonder what people here thought of us, descending on them in search of temporary respite.

*

Photography is indexical. It records what was noticed as well as what was overlooked. The camera gathers stray details, capturing not just moments but atmospheres, the in-between spaces where nothing much seems to be happening but where meaning accumulates nonetheless. It collapses time and distance, making it an apt tool with which to approach the place we knew in a different time. Its relationship with the real facilitates a closer reading of the concealed significance of details. Revisiting the photograph releases details, often unnoticed and unremarked at the time, allowing us to return to that moment and to encounter it anew.

Conventional understanding of time through photographs is different to our experience of it in daily life. While everyday life marches on, the photograph enforces the idea of time as a sequence of separate instants - decisive moments - like the blink of an eye (augenblick). Once wrested from the stream of life by the camera, they are in one sense dead or historic and, in another, stretched out in an ageless frozen state in which they can be held and examined in ways that are impossible in life. The camera offers us realism, rather than reality. Its seductive illusions of objectivity and ‘truth’ are unmoored by its tendencies towards instability and uncertainty.

*

With echoes of Chris Marker’s seminal film La Jetée, many of the photographs here suggest a stepping out of ordinary time into another, defined less by modernity and more by nature, rock, entropy, growth, petrichor and damp. They hint at temporal dislocations where moments are relived and distorted. The images point at materiality, intimating a tactility beyond the merely visual and inviting us to recall our own insistent relationship with whatever we call home. The work resists easy resolution, instead drawing attention to the ambiguity, fragmentation and resonance that home often provokes.

The work of the artists here takes Donegal as the point of departure and return, both literal and imaginative. Shifting roles between observer, participant and director, and with differing sensibilities, they lightly brush off the easy nostalgia others have towards this land. Each of them uses the lens with a restlessness and curiosity, interrogating and destabilising monolithic notions of home, belonging and distance. Poetic and beguiling, the work offers original perspectives on the intersection of personal history and geographic ambiguity, where home is at once real and unreachable.

*

Commissioned by Regional Cultural Centre, Letterkenny, Donegal 2025

Visual Artists’ Newssheet Special Issue Sept-Oct 2019

Critical Discourse

The Second Shift: CLARE GALLAGHER DISCUSSES HER PHOTOGRAPHIC RESEARCH FOCUSING ON THE BURDEN OF DOMESTIC LABOUR FOR WORKING WOMEN

“Few tasks are more like the torture of Sisyphus than housework, with its endless repetition. The clean becomes soiled, the soiled is made clean, over and over, day after day” – Simone de Beauvoir, The Second Sex, 1949

My current photographic research, titled The Second Shift, focuses on the hidden labour of housework and childcare, primarily carried out by women on top of their paid employment. I use photography and video to examine and respond to the ideas and practices of home which constitute the second shift. It is physical, mental and emotional labour which demands effort, skill and time, but is unpaid, unaccounted for, unequally distributed and largely unrecognised. Performing two daily shifts (one during ‘leisure’ hours) is the experience for the majority of working women. It also implies a hierarchy: that some people’s time matters more than others. I probe the changed and potentially more fraught relationship with home that accompanies the transition to motherhood which tends to remain after the return to paid work outside the home. Hidden in plain sight and veiled by familiarity and insignificance, the second shift is largely absent from photographs of home and family. The Second Shift is an attempt to recognise the complexity and value of this invisible work. It is a call for resistance to the capitalist, patriarchal and aesthetic systems which ignore it.

I am a full-time lecturer, part-time researcher and mother, with two teenage sons. I started researching home in the late 2000s, as the exhaustion and delirium of mothering babies and toddlers gave way to bewilderment and frustration at the gendering of my time and opportunities in ways I had not been prepared for. In my mixed-gender state school, girls went on to study engineering, medicine and law in the same proportions as the boys. Thinking the feminist battle had been won in the 1970s, we set out with expectations of equality. Where did all the promises of parity go? Of shared parenting? If we had still managed to retain the belief in gender equality in the workforce, parenthood rapidly revealed this to be an illusion.

I made a previous body of photographs, Domestic Drift, when my children were small and I was utterly frazzled by the seemingly relentless demands of motherhood, the job and housework. Wishing for things to be easier, neater, sunnier, more appealing – actually, just done – left me struggling to reconcile my everyday life with my expectations of happy family snaps, beautiful homes and Kodak moments. I felt like me, my home, my family didn’t measure up.The work became anchored in the home, in this claustrophobic, often strained and busy setting. I felt that I needed home to be clean, tidy and pleasing to be experienced properly. The fabled leisure hours, when it was all finished, would be the appropriate point at which to take it in, with all signs of mess and effort gone. However, the idea of home being the refuge from work – the place you put your feet up and crack open a cold beer – was laughable. The ordinary state certainly didn’t seem to deserve recording for posterity. By avoiding looking at home and family as a ‘work-in-progress’, I realised that I wasn’t really seeing much of it at all – neither the dirty washing and mischievous children, nor the kind gestures and playful constructions.

To confront this tension between expectations and reality, I started photographing exactly what was in front of me, in order to see it clearly and begin to appreciate it more fully, with equanimity rather than dissatisfaction. I began to face the impossibility of getting everything done, focusing instead on the non-moments, the difficult bits, the things that either barely registered amidst the busyness or were distinctly unappealing. Using a medium format film camera with a waist-level viewfinder, I photographed things the children had left – curls of masking tape stuck on a chair after some project; toy knights invading the dishwasher; a bunch of dandelions in a tissue as an apology. I took pictures of the processes of home – debris from meals and the endless laundry. I discovered the in-between moments that revealed something of the ambiguity and ephemerality of family life. I found photography effective at revealing what was right in front of me, that I was oblivious to, in the rush to get it all done.

Domestic Drift seemed to resonate with other working mothers and struck a particularly poignant chord with those whose children were grown up. Many felt that it was the ordinary moments that they recognised the most. Yet it was also these which had vanished undocumented, in the scramble of daily life. Many were angry and the same issues came up repeatedly: the substantial hidden work they did, the ingenuity they employed, the lack of acknowledgment and the pressure they felt to maintain standards in both their professional and family lives. They asked the same questions too: how might we resist the expectations that the second shift is women’s responsibility? How can we reconcile the work that we put into keeping things looking the same, with the beliefs we hold about progress? How do we point at all of this daily expenditure of time, thought and effort and say: “herein lies value”? Allen and Crow point out that “home, what it is, what it means, and how it is experienced, does not just happen”. The Second Shift therefore considers the omission of women’s domestic labour from the picture of home. Instead of hearing meaningless background noise, it finds rich significance in it. It aims to make visible what has been considered invisible – or unseeable.

Chapter in A Companion to Photography (Wiley-Blackwell 2020) edited by Stephen Bull

Boring Pictures: Photography as Art of the Everyday

Abstract

This essay examines the intersection of art, quotidian theory and everyday experience, and addresses the difficulties and potential successes that emerge in attempting to draw them together. It asks how art might facilitate our engagement with the everyday and help reveal its complexity without elevating or partitioning that experience. The author focuses particularly on photography, arguing that its accessibility, indexicality and connection with time and transience accommodate the contradictions and dualities of the everyday. Artists, photographers and quotidian theorists are drawn together here in order to ascertain strategies for examining the everyday that avoid the traditional emphasis on the surreal or strange.

Art of the everyday

Art is often seen as distant from the everyday world. The rarefication and separateness, even alienation, of the art world contrast sharply with the authenticity and democracy of the ordinary world. ‘It is possible to avoid theatre and ballet, never to visit museums and galleries, to spurn poetry and literature... Buildings, settlements and the daily tools of living however, form a web of visual impressions that are inescapable.’ (Papanek in Saito 2010: 12) Given this dichotomy, what relevance can art have for everyday life? How might it facilitate our engagement with the everyday and help reveal its complexity without elevating or partitioning that experience? I will suggest that photography might provide a mediatory role.

Photography, like the everyday, is a site of contradictions and dualities. It has contributed to changing perceptions of the quotidian and influenced the understanding of modern life. Photography rendered visible sights and subjects previously considered unimportant or uninteresting; it also contributed to the cataloguing and consumption of exotic places, events and people. It shares many of the traits of the everyday since it is frequently taken for granted, regarded as part of the general furniture of the environment and perceived to lack meaning, importance and design. As with everyday life, photography is often situated separately to art, seen as too real to contain depth or to merit deeper questioning, and is commonly associated more with function than aesthetic. Both the photograph and the everyday are customarily regarded as simple, obvious and artless; it seems one scarcely need engage one’s critical faculties to contend with them (Burgin 1982, 142-4; Price 1994, 4).

Intertwined with much of our understanding and representation of daily life, photography is, however, a somewhat difficult medium with which to reveal the unobtrusive, inconspicuous details that escape notice, given its propensity for the rapid production and seemingly insatiable consumption of images. I will propose that since its inception, photography has had a difficult relationship with the quotidian that both helps and impedes its ability to render the everyday more visible. ‘Despite the illusion of giving understanding, what seeing through photographs really invites is an acquisitive relation to the world that nourishes aesthetic awareness and promotes emotional detachment’ (Sontag 1979, 111). Guy Debord’s work, The Society of the Spectacle, suggests that the image-world fragments ordinary life: it encourages vicarious experience, stimulates material desire and determines the demands placed upon reality. A treatise on contemporary consumer culture and commodity fetishism, it points unequivocally to the role of images in separating us from our own experience as well as from other people. By identifying all life with appearances, ‘all that once was directly lived has become mere representation’ (Debord 2010: paragraph 1). If, in the spectacular society, ‘that which appears is good, that which is good appears’ (Debord 2010: paragraph 12), then the question must be asked - what happens to that which does not appear? Does this emphasis on appearance lead photography to contribute to the spectacular image and the denigration of the ordinary?

I will explore the suitability of photography as a medium for investigating and revealing the ambiguity and elusiveness of the everyday. I aim to examine a number of photographers whose work addresses aspects of the quotidian. Whether they are making use of the photograph’s indexicality to fix and retain a transient moment; exploring its potential for engaging with the nature of perception; recording creative acts in the ordinary environment; documenting the details of the small rituals and constructions of everyday life, or challenging the separateness of the everyday and the art experience, all of the artists I discuss make work that moves away from the tradition of ‘making strange’.

The photograph

Tracing the connection between photography and the quotidian, Shelley Rice describes photography as the ‘ultimate transcriber of the mundane, the unparalleled recorder of the stream of time in its transience and its banality; its images, too, select and exhibit some facet of the world, focus attention on some hitherto unnoticed corner of the real’ (Rice quoted in Gumpert 1997: 31-2). Since its invention, photography has drastically changed perceptions of ordinary life, particularly how the everyday is situated in relation to the exotic and dramatic. Early on, the camera brought back new views of far-off places and strange sights, rendering the exotic lives and lands in photographs as objects for fascinated domestic consumption and diminishing the need for firsthand experience. Along with the development of faster modes of travel and communication, it shrank the experience of distance and encouraged the acquisition of vicarious, seemingly broad, knowledge of the remote. The reach of photography was such that in 1907 James Douglas wrote that:

It is impossible to gaze upon a ruin without finding a Picture Postcard of it at your elbow. Every pimple on the earth's skin has been photographed, and wherever the human eye roves or roams it detects the self-conscious air of the reproduced. (Douglas in Schor 1992: 216-7)

So, photography may be seen to have had a role in increasing the speed with which modern life is experienced as well as a physical disconnection with place that makes it difficult to pay attention to the everyday.

Photography has had a substantial impact on visualizations of modernity, from the Impressionists onwards. Their break from tradition owed much to the influence of photography, which, as it became more rapid and portable, enabled images to be made quickly and easily, on location rather than in the studio, and encouraged more candid recording of ordinary life (see Chapter 18). The camera’s ability to seize a section of daily life in a frame without necessarily dictating the placement of people and objects inspired painters to reproduce the effects of spontaneity by composing paintings as though more casually framed in a snapshot, with people in the foreground sometimes cropped or making unselfconscious gestures (Scharf 1974: 181-8). This also suggested that the image was a fragment of a larger reality from which it had been snatched, rather than a slow, considered, self-sufficient totality. Photographic characterization of the speed of modern life persists today in the use of its qualities in representation: blur, misaligned angles, unusual viewpoints and hasty framing have all been employed to suggest a fast-moving, busy modernity.

In attempting to use photography to reveal the everyday, it is difficult to avoid the issue of the camera’s power to transform what it records. It manifests itself in several ways. The famous line in Walter Benjamin’s essay ‘The Author as Producer’ points out the troubling and seemingly relentless tendency of the camera to beautify what is in front of it, its incapability of ‘photographing a tenement or a rubbish-heap without transfiguring it’, and he decries its transformation of social injustice into an ‘object of enjoyment’ (1998: 94-5). In making permanent and reproducible that which is so essentially transient, the camera fundamentally changes the everyday by eroding its ephemerality. Transformation has historically been one of the key cultural strategies used to reveal the everyday. Beginning with the Surrealists, the idea of ‘making strange’ the ordinary and banal functioned to make it unfamiliar and thus more noticeable. Their acceptance of the quotidian as subject matter stemmed from their determinedly democratic stance – everything is real after all. By presenting what others saw as uninteresting, irrelevant or ugly in new ways, they allowed ‘the everyday to be “othered” in a move that forces a denaturalizing of the everyday’ (Highmore 2008: 30). The Surrealists’ insistence on transformation led Henri Lefebvre to attack their strategy of retreat from the banal reality before them: ‘the Surrealists belittle the real in favor of the magic and marvelous.’ (in Roberts 1998: 98) Contemporary photography maintains this tactic, often leaning on constructed imagery in an attempt to see and represent the real, depicting the familiar through its ‘defamiliarized underside’ (Baetens, Green & Lowry 2009: 81).

Conventional understanding of time through photographs is different to the experience of it in daily life. While everyday life marches on, the photograph enforces the idea of time as a sequence of separate instants, decisive moments, or blinks of an eye. Once wrested from the stream of life by the camera, they are in one sense dead or historic and in another, stretched out in an ageless frozen state in which they can be held and examined in ways that are impossible in life.

If the everyday is seen as a flow, then any attempt to arrest it, to apprehend it, to scrutinize it, will be problematic. Simply by extracting some elements from the continuum of the everyday, attention would have transformed the most characteristic aspect of everyday life: its ceaselessness. (Highmore 2008: 21)

Photography’s ability to provide a lasting image has the potential to alter the ways we re-experience the everyday through recollection. Sontag referred to this as ‘the enterprise of antiquing reality’ and to photographs as ‘instant antiques’ (1979: 80). If photographs serve as aides-mémoires then it follows that what we find easiest or clearest to recall might be what was deemed worth photographing at the time and, therefore, worth remembering in the future. This selective recording of everyday life is probably most evident in the family album. Despite accumulating huge collections of images depicting family life, the content of albums is dominated by photographs of ‘occasions’ such as birthdays, holidays, Christmases, graduations and weddings (see Chapter 17). These emblems of happiness, pride, normality and success provide an edited version of life. Rarely do families deliberately aim to document the very ordinariness of everyday life – the messy kitchen, piles of paperwork and unmade beds – or try to record more representatively the emotional spectrum of family life – the arguments, upset, boredom, frustration and yearning that go with the joy, companionship and love. In this sense, the photography that purports to represent daily life is usually a highly-managed interpretation or even a construction and serves to further the notion, consciously or otherwise, that large parts of everyday life are not valuable or appropriate subject matter, unworthy of documenting or displaying (Chalfen 1987; Bourdieu 1990, 30).

Noticing things

While the sociologist Susie Scott reiterates without question the notion that making strange is an essential premise in approaching the everyday (2009: 4), the work of French writer Georges Perec stands in direct contradiction to this position. Perec’s observations of the everyday belie the accepted reliance on Surrealist strategies. Instead, he puts forward paying attention as the deceptively facile means with which to examine it. By simply noticing the detail, action, movement and tempo of ordinary life he suggests we should be able to begin to investigate the significance hidden in plain view. Writing angrily about the sensational version of the everyday displayed in the daily newspapers (les quotidiens) Perec complains that we always seem to be talking about the eventful and extraordinary; trains and airplanes don’t appear to exist until there has been an accident or hijacking, the deadlier the better. He feels that, in our obsession with the momentous and unexpected, the historical and significant, everyday injustices are ignored in favor of dramatic ones:

What is scandalous isn’t the pit explosion, it’s working in coalmines. ‘Social problems’ aren’t ‘a matter of concern’ when there’s a strike, they are intolerable twenty-four hours out of twenty-four, three hundred and sixty-five days a year… The daily papers talk of everything except the daily. (Perec 2008: 209)

Maurice Blanchot echoes Perec’s difficulty with this paradox, saying that ‘in the everyday, everything is everyday; in the newspaper everything is strange, sublime, abominable’ (Blanchot 1987: 18).

Perec rejects the exotic for the ‘endotic’, a term Paul Virilio uses to describe ‘seeing what is not really seen’ (Virilio in Burgin 1996: 185). Instead, Perec turns his attention, and that of the reader, towards the infra-ordinaire: the realm of daily experience so utterly prosaic that it lies hidden beneath it. He finds interest and significance seemingly everywhere. ‘What we need to question is bricks, concrete, glass, our table manners, our utensils, our tools, the way we spend our time, our rhythms. To question that which seems to have ceased forever to astonish us’ (Perec 2008: 210). Perec demonstrates a stubborn attentiveness that ignores apportionment of significance or insignificance. In Species of Spaces, he outlines a number of exercises to assist the reader in their engagement with the quotidian, beginning with the directive to observe the street:

Note down what you see… Nothing strikes you. You don’t know how to see. You must set about it more slowly, almost stupidly. Force yourself to write down what is of no interest, what is most obvious, most common, most colorless. (Perec 2008: 50)

These efforts result in a kind of interrogated inventory, producing thorough lists of minutiae that are both exhaustively encyclopedic and critically considered. As a method it has parallels with the camera. Photography’s intrinsic indexicality facilitates the development of a dialogue around the borders of noticing and not-noticing and of a democratic representation of the richness of the ordinary, as can be seen in the work of Nigel Shafran. ‘The indexicality of the image connects the spectator to the messy materiality of the world’ (Roberts 1998: 104), enabling the detail in the images to expand to reveal something of the lives, needs and principles behind them. Shafran quietly observes the details of predominantly domestic daily life, recording the transient and overlooked evidence of the small rituals and constructions of the everyday: the stacked dishes and accoutrements of meals on the draining board, day after day, the arrangement of building tools, domestic utensils and the ever-changing array of cards, notes and leaflets on the table. His photographs often feature his partner and attend to the seemingly chaotic objects and surroundings of their home, through which we gain an intimate insight into her ways of doing things. She leaves a delicate tower of a sewing box perched on a stool on a coffee table, creates an improbably careful string and clothes peg arrangement with which she hangs chair legs by their castors to clean them, and labels with touching precision their odds and ends in storage, all amidst the chaos of a house in progress.

The ethnographer Bronislaw Malinowski asserted the value of attending to these small acts of everyday existence, which he called the ‘imponderabilia of actual life’ (Robben & Sluka 2012: 76). This notion is discernible throughout Shafran’s photography, which always stems from his refusal to disregard ordinary things – charity shop shelves, the array of domestic cleaning products, hair on a bar of soap – and his determination to see in them values, interests and traces of others’ ways of being and doing. In examining and recording the tiny, quiet, unobtrusive parts of daily life, Shafran makes the statement that here lies value, saying that his work represents ‘an acceptance of how things are’ (2004: 121).

Tactical Resistance

What is it that erodes our ability to engage fully and sensorially with how things are? Firmly established in the post-war years, the study of the philosophy and sociology of everyday life encompassed intense intellectual and political discussion about the effect of consumer society. Lefebvre’s critique (1991) laid the blame for the fragmentation of experience on the capitalist drive towards consumption and novelty. His theories were developed further by the Situationist International and particularly in Debord’s text The Society of the Spectacle.

When the real world is transformed into mere images, mere images become real beings… But the spectacle is not merely a matter of images, nor even of images plus sounds. It is whatever escapes people’s activity, whatever eludes their practical reconsideration and correction. It is the opposite of dialogue. (Debord 2010, paragraph 18)

‘The spectacle is a permanent opium war’, claims Debord (2010, paragraph 44), exchanging Marx’s comment on religion for commodity, and aiming to awaken the spectator sedated by a diet of spectacular images.

A capitalist society requires a culture based on images. It needs to furnish vast amounts of entertainment in order to stimulate buying and anesthetize the injuries of class, race and sex. And it needs to gather unlimited amounts of information, the better to exploit natural resources, increase productivity, keep order, make war, give jobs to bureaucrats. The camera’s twin capabilities, to subjectivize reality and to objectify it, ideally serve these needs and strengthen them… Social change is replaced by a change in images. (Sontag 1979: 178)

Photography is clearly implicated in this enterprise. ‘The camera has long been the favorite medium of the advertiser. It convinces with its realism even as it fascinates as with the magic of a dream so that even the people of our time are cajoled into worshipping the idols it creates’ (Giebelhausen in Wells 2009: 220). Sontag bolsters Giebelhausen’s criticism by accusing the camera of ‘miniaturizing’ experience (1979: 110), adding that ‘photography is the reality; the real object is often experienced as a letdown’ (1979: 147), and suggesting that reality is diminished in the face of the spectacular image.

The Situationists took Lefebvre’s concept of the everyday out of academia and brought it into the arena of cultural intervention. In focusing their attention on the organization of social space and ways to disrupt it, they moved away from the Marxist concern with time. They also transferred their attention from the relations of production to the then ‘under-theorized problem of social reproduction – the myriad activities and conditions for existence that must be satisfied in order for relations of production to take place at all’. To do this they embarked upon a series of ‘empirico-utopian experiments’ (Kaplan & Ross 1987: 2) under the general banner they termed psychogeography, or the effect of place on emotion and behavior (Debord in Knabb 1981: 8). These employed ‘a whole toybox full of playful, inventive strategies for exploring cities... just about anything that takes pedestrians off their predictable paths and jolts them into a new awareness of the urban landscape’ (Hart 2004). These tactics included détournement (appropriation or hijacking) and the dérive (drift). For the latter, Debord gives the following instructions: ‘In a dérive, one or more persons during a certain period drop their usual motives for movement and action, their relations, their work and leisure activities, and let themselves be drawn by the attractions of the terrain and the encounters they find there’ (Debord in Harrison & Wood 1997: 696). During these excursions they sought to appraise the potential of the city to be salvaged and reconstructed in a new, utopian design for living they called ‘New Babylon’. Drawn up by Situationist architect Constant Nieuwenhuys and refined over a twenty-year period, the plan laid out the foundations for a moveable, adventurous city designed to facilitate play and interaction throughout, for ‘the creative act is also a social act’ (Nieuwenhuys in Doherty 2009: 123). Constant’s aim then was to transfer creative action from the domain of the individual to the collective.

The legacy of the Situationists’ détournement strategies can be seen in the work of Sherrie Levine and Barbara Kruger and other ‘Appropriationists’ who took popular art or mass-media images and decontextualized them to critique the commodification of the artwork (see Chapter 26). The Situationists had a contradictory relationship with art, on the one hand expressing their wish to institute ‘a revolutionary critique of all art’ (Debord in Knabb 1981: 311) but, on the other, calling for ‘the end of or the absence of art, a bohemianism that explicitly no longer envisages any artistic production whatsoever’ (Anon in Knabb 1981: 107). Naomi Klein’s book No Logo details how anti-corporate activist group Adbusters applied détournement to the commercial world as ‘culture jamming’, appropriating advertising images and slogans to subvert their corporate message of consumption (2001: 279-309). Quick to learn, however, and keen to absorb the hip edginess of the work, advertisers began to co-opt the Adbusters’ methods to lend their ads the appearance of having already been détourned. As Bertolt Brecht noted, ‘capitalism has the power instantly and continuously to transform into a drug the very venom that is spit in its face, and to revel in it’ (in Ford, 2005: 158), thus reinforcing the sense of the spectacle as total and inescapable.

The cultural critiques of everyday life by Lefebvre and Michel de Certeau have used ‘this “obliquity” of the everyday, its resistance to law, surveillance and control, as a resource for radical transformation of the quotidian, producing the everyday as a category, a utopia and an idea, rather than as average existence’ (Clucas 2000: 10). De Certeau’s two-volume work The Practice of Everyday Life vividly characterizes the everyday, interpreting the problem of control, which he calls strategy, and puts forward the means with which it could be resisted, through tactics. Strategy is experienced by people as ‘a system that, far from being their own, has been constructed and spread by others’ (De Certeau 1984: 17). Tactical resistance means ‘attempting to rescue the traces, the remainders of the overflowing unmanageability of the everyday’ (Highmore 2008: 26) and escaping the hierarchy of the visual and scriptural senses to include knowledge passed on through gesture, smell and posture. This hierarchy is entrenched in the anthropological tradition, in the attempts to assert a civilized versus primitive division of the senses, with vision and sound considered more ‘European’ and the ‘lower’ senses of touch, taste and smell associated with ‘animality’ and seen as primary to the exotic savage (Pink 2006: 5). According to Ross, De Certeau reinvented the quotidian. Along with Luce Giard and Pierre Mayol, his co-authors on Volume 2: Living & Cooking, ‘their new, more contentedly phenomenological quotidian dispensed with Lefebvre’s emphasis on critique and transformation, and instead celebrated the homely practices – cooking, hobbies, strolling – of life as it is lived in the here and now’ (Ross in Gumpert 1997: 30).

De Certeau emphasizes attention to a startlingly eclectic, imaginative, inventive and ever-present practice of everyday life as the means ‘whereby potential plenitude is realized from within the everyday’s own logic rather than by its being transcended’ (Sheringham 2009: 301). He suggests that a tactical resistance to the powerful strategic forces of political, economic and scientific rationality could arise out of attention to childhood memory, the work and pleasure of cooking, the insistent presence of the body and senses, particularly those neglected senses of taste, touch, smell and of the body holding itself. And, in examining ‘ways of doing’, that is, the gestures, actions and arrangements with which we adapt to the requirements of the day, the photographic series Making Do and Getting By by sculptor Richard Wentworth presents glimpses of tactical resistance in the everyday. The work shows ‘an interest in human energy and in the resourcefulness of small and often tender acts… tiny acts of survivalism’ (Bright 2005: 210). Improvisational, situational, functional, these are also traits celebrated in Vladimir Arkhipov’s photographs of homemade gadgets. The objects speak of the people absent in the images and their ways of thinking and acting, much as Shafran’s do; they are ‘injected with an inherently human vigor’. What is evident in both Wentworth’s and Arkhipov’s work is a resistance to the rules, an unwillingness to conform to the world of appearances, signaling ‘a sort of victory over the mass-produced, materialistic modern world’ (Grasso 2012).

De Certeau’s work refined the Situationist drive towards a revolution of everyday life and with his notion of tactical resistance, built on the idea that the everyday provides the means with which we might repudiate systems of control, like capitalism or patriarchy. Developing this notion of resistance has led some artists, like Wentworth and Peter Fischli & David Weiss, to focus on adaptability and creativity in the mundane. Lefebvre argues that there is a dynamic relationship between play and art, in that both have many uses and also none at all. He describes the artwork as functioning in the everyday, like a ‘play-generating yeast… an action that suggests both the splitting down into simpler substances and the process of fermentation, agitation and disruption’ (in Johnstone 2008: 14). Play as a creative strategy fuels Yoko Ono’s 1964 book Grapefruit, a manual of instructions which includes mischievous directives such as ‘Step in all the puddles in the city’ and a map piece recalling Situationist psychogeographical mapping and their use of the ‘wrong’ maps to explore the city.

Playfulness, as a tactic of insubordination to habit and authority, was absolutely central to the Situationist movement. Its richness also emerges throughout Fischli & Weiss’ oeuvre. Using unprepossessing materials and familiar objects and sights, they have made artwork that questions the value of art as commodity and of the artist as decision maker. Their labor-intensive carved and painted polyurethane replicas of ordinary objects represent a misuse of time in the reproduction of worthless, useless things. This mischievous ‘pleasure of misuse’ (Fleck, Sontgen & Danto 2011: 23) appears repeatedly in their work. In the precariously-balanced arrangements of their series Quiet Afternoon they found they could leave the decision-making process about choosing and placing the components in the hands of equilibrium and, in the following work, the film The Way Things Go, chairs and tires escape their usual function to become elements in a chain reaction. The piece Visible World consists of a hundred hours of video footage and thousands of slides depicting unedited excursions where nothing seems to happen other than the journeys themselves. Having originally set out to photograph places of interest, they realized that they took just as many photographs on the way there, and began to question this apparent need to make decisions about what is interesting. At the heart of their work is both a surrendering to the process and a childlike irreverence for rules and conventions.

Everyday aesthetics

The relatively new study of everyday aesthetics provides criteria with which to examine how ‘an experience’, and particularly an ‘art experience’, is constructed in relation to the barely discernible mundane continuum. This intersects with phenomenology, the study of sensory experience, and with the Japanese aesthetic of wabi sabi, (Koren 2008; Richie 2007) both of which align more closely with everyday experience than traditional Western aesthetics does. Furthermore, the moral issues implicated in our attitudes and experiences of the everyday are far from insignificant, and worth examining if we are going to reveal the ordinary as valuable and important. Lefebvre’s critique of the rituals and interactions of daily life exposed them as signifiers of society and dominant social relations in a wider sense (1991). In this way, buying a bag of sugar in a corner shop could reproduce the normally hidden chain of capitalist commodity relations and production. Yuriko Saito also warns of the moral and environmental ramifications of separating the consumer from the means of production, allowing us to ignore child labor, dangerous working conditions and unchecked pollution in pursuit of shiny newness (2010: 102). Favoring the dramatic, novel, cute or spectacular also affects how endangered species and habitats are treated, with those landscapes and species regarded as attractive or exciting afforded more protection than ‘boring’ ones (Saito 2010: 59-71).

Uta Barth approaches the mundane by exploiting precisely our disregard for the everyday to make perception the central focus in her work. She is interested in our relationship to photography as a medium and its association with subject, describing the conventional notion of the camera as a ‘sort of pointing device. It makes a picture of something, for the most part; therefore it is a picture about something… The inescapable choice is what to point the camera at and the meaning that this subject matter might suggest.’ (Barth in Higgs 2004: 20) Barth chose to disengage with the focus on subject, working in her most everyday setting in order to supply a neutral visual environment. She photographs at home because home is ‘so visually familiar that it becomes almost invisible. One moves through one’s home without any sense of scrutiny or discovery, almost blindly’ (Barth in Higgs 2004: 21). By working in such a familiar and uneventful environment she questions the idea of familiarity and boredom as something to be avoided or escaped in favor of more remarkable experiences. Instead the work engages with ‘time, stillness, inactivity and non-event, not as something threatening or numbing, but as something actually to be embraced’ (Higgs 2004: 22). By playing on our oblivion to everyday surroundings in this way, Barth is able to render her photographs almost subjectless, making perception central to the viewing experience. This use of the everyday as a means to reject external subject matter in order to evoke a perceptual experience in the viewer echoes Virilio’s notion of the endotic since it is concerned with renewing ‘the very conditions of perception’, witnessing that which is within, as opposed to the exotic which lies outside. (Virilio in Burgin 1996: 185)

Using the camera to preserve the remains of meals, Laura Letinsky utilizes the ‘photograph’s transformative qualities, changing what is typically overlooked into something beautiful’ (Letinsky in Newton & Rolph 2006: 77). By fixing and retaining an overlooked moment of time we are able to study and admire the transience of the everyday. In her work, the paradoxical nature of photography’s relationship with time becomes unavoidable. The photograph at once attests to our impermanence, our ‘mortality, vulnerability, mutability’, and transcends it. ‘All photographs testify to time’s relentless melt’ (Sontag 1979: 15). The images cause us to consider the rapid transformation from raw ingredients to occasion for nourishment and social interaction, to mess and leftovers waiting to be cleared away and the cycle started again. Photographing this stage in the continuum from alluring freshness to repulsive decay allows us to expand the moment, extending in imagination back in time to envisage the preparation and consumption that went before the image and the resumption of cleaning and disposal that follows it. The photographs transform these scraps of meals, establishing value through looking at and photographing them.

Letinsky’s series echoes the philosophy of the wabi sabi aesthetic. Arising from Taoist and Zen Buddhist ideas about acceptance of reality and non-attachment, ‘wabi sabi is ambivalent about separating beauty from non-beauty or ugliness. The beauty of wabi sabi is... the condition of coming to terms with what you consider ugly’ (Koren 2008: 51), of learning to appreciate whatever one faces, and not engaging in the hierarchical thinking that deems some things better or worse, more valuable or less significant than others. The wabi sabi tea ceremony encompasses a number of ideas pivotal to attending to the everyday. It emphasizes an appreciation of functional utensils, along with their consequent ageing and degradation. In this way, the crude, even chipped accoutrements, minimal decor and meager portions of food in the tea ceremony represent the recognition that insufficiency and difficulty are facts of life and enable a view that appreciates value and significance in the ordinary. In seeing worth in ageing, wear and damage, wabi sabi also contradicts the Western idea that there exists such a thing as an optimal state, as in pristine newness, a clean tidy room, a plant in flower or a sunny day, from which they only deteriorate.

While Western aesthetics demarcates experiences worthy of contemplation through recognized conventions like the use of frame, the wabi sabi experience is frameless, so that the sounds, smells, feelings and sights, whether of birds, rain, cold or traffic, become an integral part of that encounter. John Cage’s piece of blank score 4’33” is an example of a frameless aesthetic experience, akin to the wabi tea ceremony, in that while it is framed explicitly by a period of time, the duration makes space to contemplate the everyday occurrences such as coughs, shifting in seats, physical sensations and emotions that are normally external to the art-centered aesthetic experience. In his music, the artist’s function shifts ‘from that of the prosecutor of meaning to that of the witness of phenomena… waiting, listening and accepting’ (Kaprow 2003: xxiv).

The sensible

Where wabi sabi concerns itself with the aesthetics of function rather than spectacle, for the writer and academic Jacques Rancière aesthetics and art are more closely associated with politics. For Rancière, aesthetics

denotes neither art theory in general nor a theory that would consign art to its effects on sensibility. Aesthetics refers to a specific regime for identifying and reflecting on the arts: a mode of articulation between ways of doing and making, their corresponding forms of visibility and possible ways of thinking about their relationships. (Rancière 2013: 4)

His analysis of perception, particularly of the systems of divisions that bound what is perceptible, led to a number of interesting propositions, the most relevant to this study being the ‘distribution of the sensible’. Constituting the fabric of recognizable experience, the sensible is that which can be sensed, heard, felt, seen and noticed within a particular aesthetic-political system. It is what is discussed in conversation, depicted in television programs, heard as music and exhibited in art galleries. Controlled, according to De Certeau, by strategy or, as Pierre Bourdieu suggests, by complicit social silences (Tett 2010: xii-xiii), it renders marginalized voices as unintelligible noise and keeps invisible those activities considered undeserving of attention. Rancière proposes that the sensible is distributed - ‘policed’ - by organizational systems that implicitly separate the protagonists and the excluded.

The police is thus first an order of bodies that defines the allocation of ways of doing, ways of being and ways of seeing and sees that those bodies are assigned by name to a particular place and task; it is an order of the visible and sayable that sees that a particular activity is visible and another is not, that this speech is understood as discourse and another is noise. (Rancière 1999: 29)

Ben Highmore gives the example of female hysteria in the nineteenth century, in which women’s complaints about marital conditions were defined as senseless babble or deranged ravings (2010: 48). However, as that example indicates, distribution is not immutable. A ‘dislocation’ in the distribution of the sensible occurs when people, things or experiences gain an audience or presence and become noticeable.

The task of political action, therefore, is aesthetic in that it requires a sense perception so that the reigning configuration between perception and meaning is disrupted by those elements, groups or individuals in society that demand not only to exist but indeed to be perceived. (Panagia in Deranty 2010: 96)

Rancière suggests that art has the potential to disrupt the distribution of the sensible. He urges erosion of the aesthetic paradigm that partitions ‘pure’ art from the decorative and functional arts, following the examples of the Arts and Crafts movement and its successors Art Deco, Bauhaus and Constructivism (2013: 10). Indeed it is the very nature of partitions that so exercises Rancière: ‘this dividing line has been the object of my constant study’ (2004: 225). He rails against hierarchies of representation, preferring instead an aesthetic system that is uninterested in a hierarchy of significance and which appreciates equally the sounds of, say, the water pump and the cathedral organ (Highmore 2010: 46). The redistribution of the sensible is therefore a continuing realization of the potential for everything to be significant.

The aesthetic revolution is the idea that everything is material for art, so that art is no longer governed by its subject, by what it speaks of; art can show and speak of everything in the same manner. In this sense, the aesthetic revolution is an extension to infinity of the realm of language, of poetry. (Rancière 2003: 205)

Paying attention to the ordinary, according to Rancière, is to engage in the political action of distributing and redistributing the sensible. He emphasizes the value of attending to the insignificant sounds and occurrences of everyday life in effecting a ‘new education of the senses’ (2009: 6), one made up of ‘sensory micro-events, that new privilege of the minute, of the instantaneous and the discontinuous’ (2009: 10). For him, everyday artforms such as photography and cinema, as well as art of the everyday, most freely permit dislocation of the sensible. Their realism, as well as proposing an equality of representation, suggests that there is ‘an inherent splendor to the insignificant’ (Rancière in Highmore 2010: 51).

Both aesthetic and political deeds, whether enacted by artists, politicians or laypeople, redistribute the sensible in ways that reshape sensorial perception. One redistribution might be the profound effect photography had on ideas of representation, enabling images to be made of factories, ordinary activities and the working class; themes which had hitherto been a matter of insignificance to the wealthy commissioners and consumers of images and deemed unworthy of the effort and time required to record them. Dislocation therefore makes visible what had been considered invisible - or unseeable. The development of cameras and film allowed the photographic image to be treated without the preciousness of a painting, and encouraged a wider range of subject matter to be recorded. Considered a popular, democratic medium in contrast with the more rarefied arts of painting and sculpture, photography expresses an ‘unpreciousness’ of subject matter and resulting artefact. Lewis Hine was ‘a crusader with a camera’ (Badger 2008: 46) who turned his attention, and the fidelity of the photograph, to the exploitation of child laborers during the early 20th century in order to advocate an end to their abuse. Eugène Atget photographed the streets and shops of Paris as it began to change rapidly in the face of modernization. Did Atget realize these details were soon to disappear, forgotten and otherwise unrecorded? His neglect of the spectacular and monumental, such as the Eiffel Tower, in favor of the ordinary streets he knew well, suggests that perhaps he did.

Conclusion

Photography’s innate qualities seem to offer the means of engaging with and appreciating the everyday. Its indexicality facilitates the recording of vast quantities of detail and, even if that richness of detail is shrouded in familiarity in the moment, the photograph’s democratic realism allows us to notice, re-experience and re-evaluate it through the image. Existing both as art form and as ordinary tool, photography is probably the creative medium most embedded in everyday life. It is accessible, rapid and almost ubiquitous. A capability of many common devices, it offers the possibility of a more immersive experience of representation.

The impact of digital photography on our understanding, production and consumption of images is difficult to quantify, given the speed of its evolution. Work made by artists and photographers which appropriates the enormous quantity of images in the public domain has proliferated in recent years (see Chapters 5, 10 and 28). Writer and editor Fred Ritchin underlines the growing need for these ‘"metaphotographers" who can make sense of the billions of images being made and can provide context and authenticate them. ‘We need curators to filter this overabundance more than we need new legions of photographers’ (Ritchin in Lybarger 2013). Interested in ways of making sense of the panoptic vision of Google Maps and Streetview, Mishka Henner, Michael Wolf, Jon Rafman and Doug Rickard use photographic images taken from the internet, developing their own filters with which to sieve out data from the morass. Erik Kessels, Penelope Umbrico and Joachim Schmid have all made installations of photographs from social and image-sharing networks. For Kessels’ piece Photography in Abundance he printed every image uploaded to Facebook, Flickr and Google over a 24-hour period – one million in total – producing an avalanche of photographs in the gallery to comment on the overwhelming scale of private digital photography and its slide into the public domain. ‘We’re making more than ever, because our resources are limitless and the possibilities endless. We have an internet full of inspiration: the profound, the beautiful, the disturbing, the ridiculous, the trivial, the vernacular and the intimate’ (Cheroux, Fontcuberta, Kessels, Parr & Schmid 2011). Umbrico’s compilation, 8,799,661 Suns From Flickr, and Schmid’s series Other People’s Photographs, both make the point that, despite these boundless possibilities for picturemaking, the content and conventions of most digital photographs are narrow. This highlights the continuing relevance of Hans-Peter Feldmann’s comment: ‘Only five minutes of every day are interesting. I want to show the rest’ (Feldmann in Johnstone 2008: 121)

The growth of digital photography has, however, undoubtedly altered the concept of the family album from a domestic image library of special occasions to a fluid, much more prolific and substantially more public showcase, distributed through the internet on blogs, social networks and online photo-sharing sites like Flickr and Instagram (See Chapter 16). This use of digital photography

signals a shift in the engagement with the everyday image that has more to do with a move towards transience and the development of a communal aesthetic that does not respect traditional amateur/professional hierarchies. On these sites, photography has become less about the special or rarefied moments of domestic/family living… and more about an immediate, fleeting display of one’s discovery of the small and mundane. (Murray 2008: 151)

I have touched upon what Johnstone calls the ‘thorny issue’ (2008: 17) of making art of and about the everyday without eroding its everydayness. Some writers, including the everyday aesthetician Saito, believe that ‘presenting a slice of everyday life as a work of art does seem to pose an unbridgeable gap between art and life’ (2010: 251). Nonetheless, I hope my argument of the close link between photography and the quotidian has demonstrated the medium’s potential to overcome that rift. The works of the theorists discussed here suggest ideas that might help develop an art that retains its quotidienneté: by being mindful of the conventions of aesthetics, such as permanence, framing, context and their consequences, by integrating function and resourcefulness, and by attending to the rhythms and habits of ordinary life.

British Journal of Photography

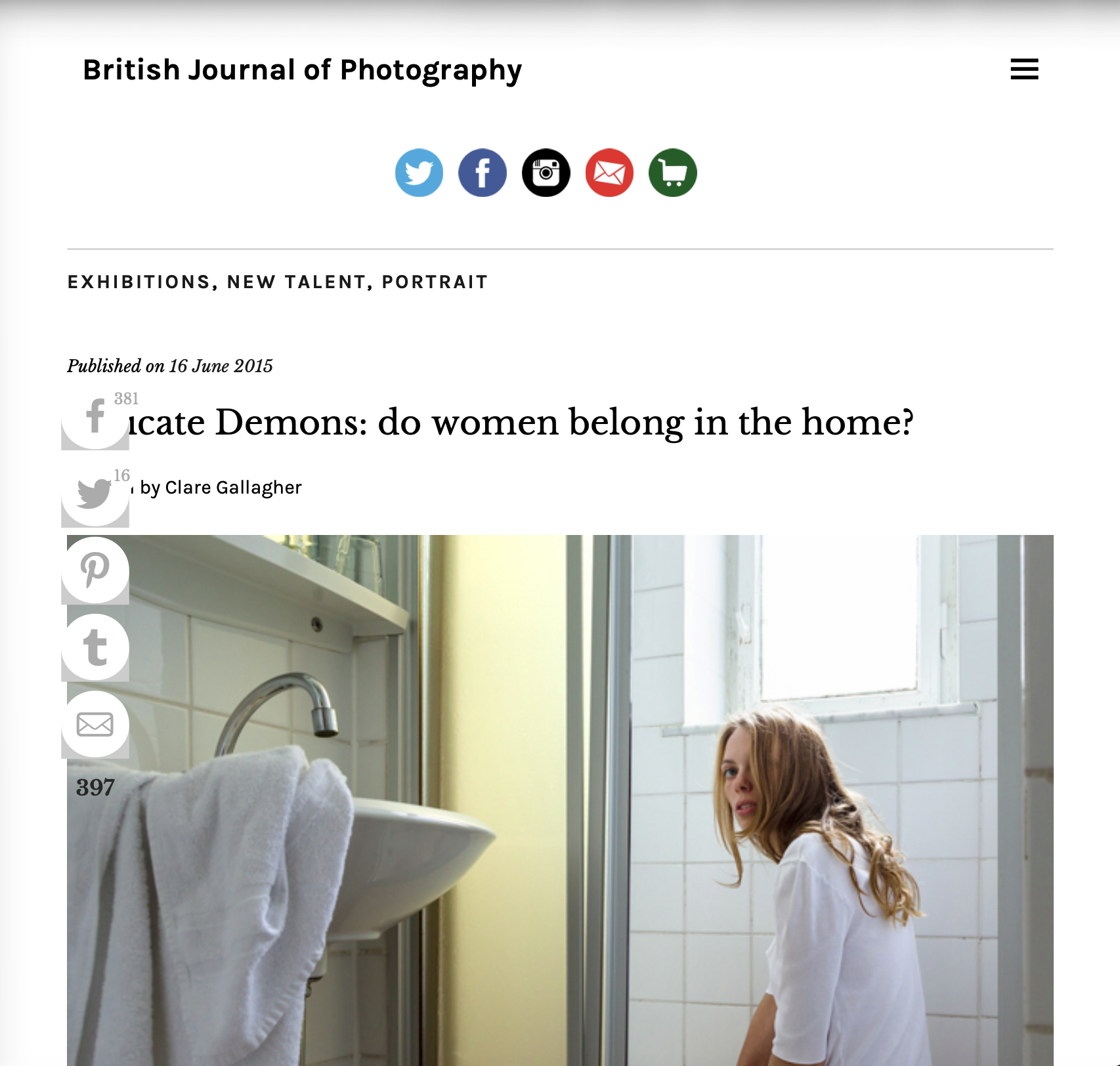

Delicate Demons: Do Women Belong in the Home? (2015)

Delicate Demons is a collaborative, ongoing project between Finnish photographers Satu Haavisto and Aino Kannisto, in which women are meticulously staged in domestic spaces.

The spaces in the photographs are tight, with a room corner in most of the scenes, compressing the viewer and the subject into an uncomfortably proximal relationship and emphasising the sense of home as a potentially oppressive place.

The women appear as mysterious characters, deep in thought. They feel heavy and complicated, physically embodying difficult emotions and experiences.

The gaze of many of the women is strikingly intense. In one image, Woman on Balcony, her stare out of the frame feels somewhat over-constructed until, with a jolt, we see in a reflection she is in fact gazing directly at the camera.

Face on, her look is more vulnerable, more anxious and raw. Props and settings combine to hint at troubling, ambiguous backstories: one figure clutches a kitchen knife, barely visible between her knees.

Delicate Demons comes from the same vein as Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s novella The Yellow Wallpaper, in which the apparently innocuous wallpaper becomes a metaphor for woman’s confinement in the home.

Haavisto, who was born in 1975, and Kannisto, born 1973, make work which feels less theatrical, expansive and allegorical than their contemporary Gregory Crewdson, the American photographer known for his elaborately staged scenes of American homes.

This work eschews the cinematic feel of Crewdson’s imagery, evoking instead a feeling of disturbing intimacy.

Both artists graduated from the prominent Helsinki School at Alvar Aalto University, a department which also produced their contemporary Elina Brotherus. Alvar Aalto’s photographers are known for their cool, careful style and frequent use of the figure to embody experience in the landscape.

Haavisto and Kannisto find the process of collaborative working an opportunity to confront and negotiate their intuitive, unchallenged methods of practice.

While they share the development of ideas in the project, they have demarcated roles in the realisation of the work, with Kannisto designing each set and Haavisto directing the model. They were drawn to these scenes of women washing themselves, doing dishes, perched uneasily or lost in anxious thought, saying they felt these experiences were rarely represented, perhaps because they were seen as “too private, in an embarrassing or banal way”.

Delicate Demons serves to contradict the facile notion of home as tranquil haven and as a naturally feminine space.

The overall sense of the series is of the unheimlich, the uncanny or unhomely, in which the familiar contains aspects which are both known and strange, comforting and frightening.

Delicate Demons, by Satu Haavisto and Aino Kannisto, is on show at the Red Barn Gallery, 43B Rosemary Street, Belfast until 28t June. Open from Tuesday to Saturday, 10-5pm, as part of Belfast Photo Festival

Published 16th June 2015